Published: Sept. 25, 2016

It’s not what you say; it’s how you say it. Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump would be well advised to remember that adage when taking the stage at Hofstra University in Hempstead, N.Y., Monday night for the first U.S. presidential debate.

A person’s body language can have a big impact on our perception of them. So, let’s break it down.

If you’ve watched Trump for any length of time, you’ll notice he uses a lot of pointing, slicing, stabbing and other sharp motions. Turns out they affect the part of our brain that deals with emotions, known as the limbic system.

“Those read in the limbic brain as symbolic weapons, so they come across as both powerful and aggressive,” said Patti Wood, renowned body language expert and author of Snap: Making the Most of First Impressions Body Language and Charisma.

Clinton, she says, could not get away with those gestures. She opens her palms and lifts her hands and her arms.

“She does more what I call up gestures that typically appear shoulder up, but at least up above the waist,” Wood said. “And those we perceive as being positive, victorious, joyful, winner status.”

Wood says women have to walk what she calls “the ‘b’ line,” referring to the slur commonly used against women.

“We can’t be too passive, and we can’t be too powerful or aggressive,” she said.

She says when Clinton has communicated more forcefully in the past, her likability factor has dropped.

Feel, show, say

Wood says candidates’ body language can also profoundly affect us when they believe what they’re saying, a concept she calls “feel, show, say.” Trump, for instance, shows that he believes what he says.

“When you believe something, you feel it in your limbic brain, you show it in your non-verbals that come from your limbic brain, and then you go over to your neo-cortex and say it,” she said.

“So, when you’re listening and watching someone who believes what they’re saying, there’s a synchronous, almost musical way that it’s presented to the brain that tells me: this person is telling me the truth. So, we believe it — if they believe it.”

Clinton, says Wood, stays more in her neo-cortex (the “say” part): she’s rational, brilliant and extremely prepared, but she doesn’t necessarily go to emotions.

Wood says all this body language figures into our desire to have the most powerful and charismatic leader. Charisma factors include: credibility, likability, attractiveness and power. And if someone is high in those last three factors, it overrides the brain’s ability to tell whether or not that person is credible.

Read: powerful gestures can trump implausible words.

Motivating the voter

Body language expert Mark Bowden says this U.S. presidential election is not about the swing vote. It’s about getting people to vote at all.

Turnout in the 2012 presidential election was 57.5%, down from 62.3% in 2008.

“So, the body language involved is how you get people up off the sofa. That isn’t necessarily about being liked; that’s about being motivational,” said Bowden, who is based in Toronto but coaches executives and politicians around the world.

“Donald’s idea about motivating people is that it’s all really bad, and it will get worse unless we stop Mexicans. So, he’s taking the stance of someone who will aggressively stop people from coming in.”

Politicians find the physical action that goes with the psychological metaphor, something called embodied cognition.

With Trump, that means pointing the finger, using a shoving motion as if he were pushing people away and his “you’re fired” gesture from The Apprentice reality TV series — to show he’s firing the current leaders and their way of running the country.

Bowden says Trump’s gestures are up in the chest area, which raises the audience’s heart rate and blood pressure, gets them revved up. He says if you’re not a Trump fan, this won’t entice you, but if you want an authoritarian leader, he’s your guy.

“Hillary Clinton’s way of motivating people is: We’re all right. America is a great, great country, and don’t let that guy (Trump) mess it all up. It won’t be great if you let that guy in. And you need to get off the sofa and vote unless you want the place messed up.”

Translated into body language: “She’s all smiles, nice and calm on the whole, but pointing aggressively when it comes to Trump. So, her aggression is towards an individual: her opponent,” said Bowden.

The upper hand in the debate

Now, let’s talk about the presidential debates. When the candidates walk on stage, watch for that opening handshake. Research shows the perceived winner of the debate can ride on who grips their opponent’s upper arm, says Patti Wood.

“Automatically, the audience goes: that’s the more powerful person. They won.”

Bowden says when he coaches politicians in debates, he makes sure they enter the stage from the left. Why? So when they shake hands with the opponent, their arm faces the audience and looks bigger. A winner.

So much of the message is determined by what we see. Remember the first televised debate between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon? Nixon appeared ill and sweaty after a recent hospitalization while Kennedy looked cool and confident. People who listened on the radio thought Nixon won, but the TV audience said Kennedy.

Body language during that debate on Sept. 26, 1960, was just as important as it will be in the first presidential debate of this election cycle on Sept. 26, 2016. (And how crazy is it that they’re on the same month and day?)

Bowden coaches politicians to put their hands not too low or too high but in front of the belly: the so-called truth area, the centre or gravity. He says it shows someone who is calm and assertive, in control of their environment. He’ll expect both candidates to project this during the debate.

‘Trump has the upper hand because when he gets aggressive, it’s way more noticeable.’– Mark Bowden, body language expert

But he’ll also watch for Trump to become aggressive when speaking about what he sees as the invasion of America by outsiders, and for Clinton to turn aggressive when targeting Trump.

They’ll both need to motivate people enough to get them to vote.

“Trump has the upper hand because when he gets aggressive, it’s way more noticeable,” Bowden said. “We’ll watch aggression way more than we’ll watch someone being more passive.”

Wood says anger is a high motivator. “We tend to be persuaded more by anger. People who are angry will go out and vote. It pulls us to the polls.”

While this could point to a Trump victory, positivity is also a powerful motivator. Maybe the United States is finally ready for a female president.

(Mike Segar/Reuters)

(Mike Segar/Reuters) (Brian Snyder/Reuters)

(Brian Snyder/Reuters) Research suggests that the person who grips their opponent’s upper arm, as Barack Obama did to Mitt Romney in their Oct. 3, 2012 debate, literally gets the upper hand in the debate even before a word is spoken. (Charlie Neibergall/AP)

Research suggests that the person who grips their opponent’s upper arm, as Barack Obama did to Mitt Romney in their Oct. 3, 2012 debate, literally gets the upper hand in the debate even before a word is spoken. (Charlie Neibergall/AP) (Associated Press)

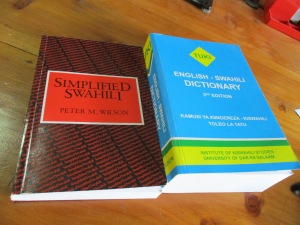

(Associated Press) Swahili, which I tried to learn during my short time in Tanzania, is easy peasy compared to Amharic, the official working language of Ethiopia.

Swahili, which I tried to learn during my short time in Tanzania, is easy peasy compared to Amharic, the official working language of Ethiopia. I’ve tried to memorize some of the symbols, a mass of lines and squiggles and circles that are somewhere between those Olympic sport pictograms and charm bracelets. I’ve tried equating the image – say a person taking a flying leap – to the sound — ño (read: noooooo!). It is somewhat effective. But tedious. So I stopped.

I’ve tried to memorize some of the symbols, a mass of lines and squiggles and circles that are somewhere between those Olympic sport pictograms and charm bracelets. I’ve tried equating the image – say a person taking a flying leap – to the sound — ño (read: noooooo!). It is somewhat effective. But tedious. So I stopped.

‘Kiswahili’ comes from the Arabic word for boundaries or coast, and with the prefix “ki”, it means coastal language. It’s a mixture of words from Arabic and East African Bantu but also contains Persian, English, Portuguese, German and French words, absorbed through contact over five hundred years.

‘Kiswahili’ comes from the Arabic word for boundaries or coast, and with the prefix “ki”, it means coastal language. It’s a mixture of words from Arabic and East African Bantu but also contains Persian, English, Portuguese, German and French words, absorbed through contact over five hundred years.